Atchaaaqluk, Itga’raleq, Beach Greens

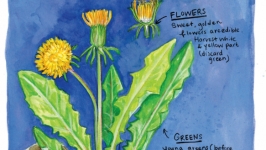

Whenever I walk along an Alaska beach in springtime, I search for opportunities to nibble on an abundance of seaside snacks. Some of the most ubiquitous edible treats are brightly colored beach greens (Honckenya peploides). Mounds, mats, and dense patches of this hardy plant can be found loving life in the sand and shells along the sea. These cheerful greens have succulent light-to-medium green pointy leaves that grow opposite each other with two leaves per node along a juicy light-colored stem.

Springtime is primetime for beach greens, which are rich in vitamins C and A. I start looking for them when the snow begins to melt, and I harvest the shoots before they begin to flower. The crunchy stems and mild leaves taste refreshing, with hints of ocean flavor. By the time tiny white starry flowers begin to form, the plants have gotten bitter, tough, and stringy. In her book Discovering Wild Plants: Alaska, Western Canada, the Northwest, Janice Schofield Eaton mentions that the spherical seedpods can be “ground up and used to extend flour supplies, or sprinkled as a garnish on various foods.” Collecting and processing can be tedious, so another option is to leave them to seed a new generation of plants.

From the north slope to the Northwest Arctic, down the coast to Southwest Alaska, from the Kodiak Archipelago and Aleutians, and all the way to Southeast Alaska, this coastal resident goes by many names because wherever it grows, people have a relationship to it. Years ago, friends in Kotzebue introduced me to this plant by its Inupiaq name atchaaqłuk. They shared stories about atchaaqłuk prepared in the traditional way, fermented until sour and stored for winter in large wooden barrels. Anore Jones’ book, Plants That We Eat: Nauriat Nigiñaqtaut, includes more details about traditional preparations. Laureli Ivanoff of Unalakleet also shares her family history with the plant in a recent story in High Country News.

One of my Inupiaq friends in Nome shared a contemporary preparation of beach greens using a quick-fermenting process. To my surprise, the result tasted fragrant, like canned peaches. In Southwest Alaska, Yup’ik friends in Hooper Bay introduced me to these plants as itga’raleq. There, the greens are served with seal oil or added to akutaq, which is a traditional dessert that blends berries with fat, and variations of fish and plants.

Similar species grow on other northern beaches in Canada, New England, Iceland, and Scotland. In addition to beach greens, other common names include beach chickweed, sea chickweed, sea pimpernel, and seabeach sandwort in English, and fjoruarfiin Icelandic.

For respectfully wild harvesting beach greens, as with any other plants, I have learned from my teachers to begin with a mindset of respect and gratitude, as well as one of observation and caution. It is important to be able to identify the correct plant. For clean and safe harvesting, I search for beach greens in areas far away from trails and places where people and dogs might have contaminated them. I also harvest according to what I need and what I am prepared to process and store with the amount of time and space that I realistically have. I choose young, healthy-looking leaves and stems, admiring their shiny yet velvety texture. I avoid plants that are diseased and weak looking, or that are yellowing and in the flowering stage.

To reduce the impact of the harvest on any one population, I spread out my harvest to multiple patches and take only a small amount from each one. Using scissors to snip or fingers to carefully pinch off the shoots, I make sure the roots of the plant stay in the ground with minimal disturbance because they are perennial plants that will grow back. Each year, I return to the same group of plants to observe how my harvesting affects them over time.

In the kitchen, I immerse the plants in several rinses of water to remove all sand. Because the plants can be salty and sometimes bitter, I like to combine beach greens with other ingredients. They are delicious raw, so I may chop them up and add them to a salad. They can be steamed or sauteed or added to stir frys or soups. And when I am with my friends in Western Alaska, we gather and ferment atchaaqłuk or itga’raleq so we can savor the memories of summer harvesting when we enjoy them in winter.

Over the years, the beach greens themselves have gifted me countless teachings. I have learned to recognize them as a familiar friend by their local name whenever I am on the coast. I admire their resilience, growing in lonely patches by the sea, withstanding immersion in saltwater, windstorms, and trampling by passersby. And yet the plants persist with roots holding strong to the sand. Beach greens’ tenacity enables them to stay long enough to stabilize the substrate where they grow, nourishing the ground and making it possible for other maritime plants to follow and even take over the habitat. I marvel at the plant’s many names and contributions to dishes and food traditions throughout Alaska’s coastal communities and other northern places. Rugged and nourishing, salty and sweet, resilient and generous, beach greens have many superpowers; may we celebrate them this spring.

This story was first pubilished in Issue 27, the Spring 2023 edition of Edible Alaska.